Contemporary artist Leasho Johnson came to Chicago from his home in Sheffield, a small town on the outskirts of Negril in Jamaica to attend The School of the Art Institute Chicago in 2018 to get his Masters of Fine Art in Painting and Drawing. Growing up with a father who was an artist encouraged him to explore his artistic mind and delve into paint, collage, and sculpture as a medium. His detail oriented style, paired with his eagerness to constantly push and study new art forms allowed him to not only challenge, but reclaim Western narratives of Blackness and queerness. Moreover, the freedom of moving outside of the boundaries of one’s hometown has unearthed unknown aspects to his artistic storytelling.

In our conversation, Johnson traces his creative origins back to his family, and follows that journey all the way to this incredibly transformative time period we’re living in. Thankfully, the pandemic hasn’t shifted the way he’s shared his work too much. To Johnson, the Caribbean can find itself isolated from a lot of the greater world due to its location and untold histories. Social media became the tool Johnson used to communicate the themes central to his upbringing, due to the fact that social media and online movements have allowed a freedom to create worlds unimaginable in person. Johnson’s articulations of Black queerness now not only reside in an unapologetic online space, but connect the threads of his life in Jamaica, to his current burgeoning career here in Chicago and beyond. His latest exhibit Only When It’s Dark Enough Can You See the Stars’ was on display at FLXST Contemporary in September 2020, and is still available for viewing online.

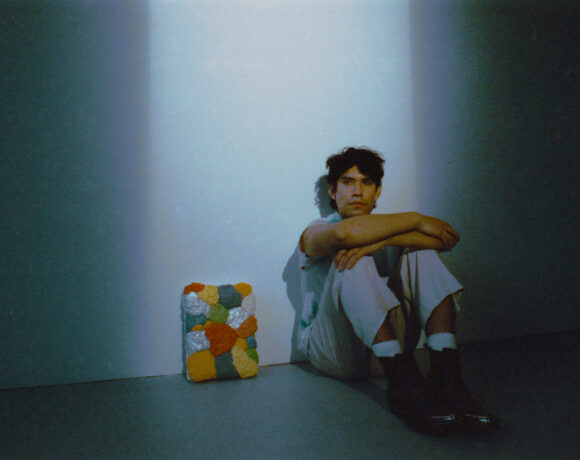

Photo of Leasho Johnson by Raquel Pérez Puig

AMFM: Where did your journey as an artist begin? When was the first time you called yourself a full time creator?

LEASHO JOHNSON: I’ve always been a creator in a way. I grew up in my dad’s studio as he was an artist himself in the ‘80s. I would observe him painting and doing graphic design gigs. At that time everything was done by hand. He was truly a Renaissance man thinking about back then now as an adult. He would be doing painting, graphic design, and sculpture. I don’t think I had any other choice than to be an artist. My ability was noticed in almost every stage of my education from early childhood, to prep school, to high school. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be an artist in the beginning. I wasn’t sure if it was a viable career option, the education system at the time pushed for academic abilities like Math and English. I felt a bit marginalized as abilities like my own didn’t seem to have any much value or place at that time. My father was adamant I went to art school, so when I finally enrolled in art school in 2006 at the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts, I studied Graphic Design, feeling as if it was the best use of my ability. Ironically, I sold a lot of paintings of landscapes and ‘touristy’ stuff, to help with my expenses during those four years. I applied my abilities to all facets of creating. Two of my other creative friends and I, who are now architects, got an opportunity to revitalize an old hotel on the cliffs in Westend Negril. It was multiple buildings with single or double occupancy, there was a bar and we did some wall art to the lobby area. We created various themes to differentiate the multiple buildings that housed the rooms, each building had at least four rooms. That I would say is the first big artistic role I had professionally. I think I was about 23 at the time. We lived there and visualized the themes, we chose fabrics, got furniture made, and came up with color schemes. We were employed by local entrepreneurs — they really gave us the full reign to reimagine the entire hotel. That was during undergrad when I graduated with my degree in Graphic Design in 2009, I worked for an advertisement agency. That same year, I also took part in an exhibition called “Rockstone and Bootheel” at the Real Art Ways in Connecticut. That’s when I would officially say I started to take art seriously. For most of those years after graduating from undergrad, I was dabbling in fashion as well. I was working for a local fashion designer, Barry Moncrieffe, who was a mentor and a dear friend. He was a retired dancer by career who was also the artistic director of NDTC (National Dance Theatre Company). I would do one show for him ‘Caribbean Fashion Week’ every year. While I continued my day job at the design studio and still paint in my studio/apartment, I’ve been doing that for about 18 years prior to pursuing my MFA.

“Those without whom the earth would not be the earth” 25.5 x 33.5 inches, charcoal, distemper, watercolor, acrylic, oil, collage, gesso on paper mounted on canvas, 2020

AMFM: You were born in Jamaica and now live in Chicago. For how long did you live in Jamaica before moving to the US and how does your identity in these two places inform your work?

JOHNSON: Yes, till I was 33. I came here through a scholarship from SAIC, that was 2018. Seems like that was yesterday. Well, before coming here I was using the language of art to critique postcolonial identity, looking specifically on gender dynamics and dancehall culture in Jamaica. I focused a lot on humor, and the caricature of life that we envelope ourselves in to cope with the contradictions we encounter socially. I was thinking of my immediate audiences and using the art as social commentary. Thinking about self-acceptance and private versus public and international ideas around Black Caribbean identity. When I came here, my intent was to find a way to expand myself from a kind of cultural vacuum and add it to a larger dialogue. Since I’ve been here, I feel I can be more personal and fearless about my true intentions, which is to talk about my personal experiences, dealing with not just my Blackness but my queerness. Covering up that aspect of my identity is reflexive, and even the work suffers from that. I am much happier now with what I’m doing. I’ve revisited the first art material that my father taught me to use, watercolor. Mastering watercolor is very challenging, but the brush dexterity you gain goes a long way. I’ve used various mediums for various reasons but because of this connection I have with watercolors it has now become a staple in my current practice. I’ve also started to articulate my own personal stories, mining memory, and occurrences that shaped my vocabulary in art-making. The distance being in Chicago really gives me the chance for clarity.

Young stud in a hat, 22″x 30″, watercolor, oil, and collage on paper, 2020.

AMFM: I noticed the use of the body in a lot of your work. Why is that representation so necessary for your expression and how are you trying to reimagine the body in your work?

JOHNSON:The body came into importance by default, thinking about dancehall culture and its nuances, like gender politics and performance, which evolved into dissecting the histories and contentions that are contained in that. Then, of course, navigating these terrains in a Black body, having queer desires, the mechanism of survival that’s afforded by being of both ‘spaces’ sometimes are not afforded to both, so I am reimagining what that body could look like. I don’t want to represent the Black body in likeness, as I feel the freedom to not have to depict likeness eases up the expectation of painting, and opens up a broader conversation around both Blackness and queerness. Also, the tradition of portraiture still is marked by the aspects of colonialism, and I feel if I need to ‘represent’ something that is not occupying the same spaces as that history. The re-imagination I choose to anchor the work in is more about mythology and transcendence. I’m thinking about the historical, like Anansi, the mythological deity of stories and mischief. The culture, like dancehall or Voodoo, as ways of evoking something through the Black body that defies representation. Probably even exploit the demonization the West has about Blackness. This gives me space to depict Black queer bodies free from social expectations and scrutiny.

‘Bangee #2’ 25.5 x 33.5 inches, charcoal, distemper, watercolor, acrylic, oil, collage, gesso on paper mounted on canvas, 2020

AMFM: You’ve been in exhibitions and showed your work all over the world. How much does travel and physical space play into the work you create or who it’s created for?

JOHNSON: Travel is important to art in general. It plays a huge role in not just how the art is seen, but also how you the artist see the work, and how that informs the art-making. Traveling for me opens up and reconnects aspects of history, identity, and perspectives. Some knowledge can only be acquired through experience. Of course, coming here to Chicago informed my work greatly. Presently, I would say the work is for those who cannot find space, both out there and in here (the mind). I create contemporary art because it has a way of challenging perceptions. I had a hard time fitting in my own spaces at home and especially in the greater mainstream society. I thrived from creating space in the work, and through the work, I found solace. And I hope that’s what it does for people in my community.

Deloris 11.5 x 14.5 x 2 inches, Charcoal, watercolor, acrylic, oil stick, oil, and gesso on paper mounted on canvas, 2020

AMFM: This year has been traumatically long for many of us. Have you revisited the way in which you create and share art due to not only the new practices in place during a global pandemic, but also the current conversations surrounding systemic racial injustice?

JOHNSON: In a way no, and another way, yes. No, I have not really changed how I create and share. Online was the main way from before the pandemic because being from the Caribbean, we are always isolated from the larger art world. Social media becomes a bridge for informing and connecting as a whole. My work looks at systemic injustice indirectly, and deals with alienation unique not just to LGBTQ problems, but more from a position that is unique to our race all over the globe. It’s hard to describe my feelings about racial injustice. Black people globally are marred with violence and inequality. It is no surprise that this was an international movement and not (just) isolated to the States. I hate to admit that this is something we have come to expect growing up Black. It’s enraging that after so long a history of fighting for equality, we still have such a long way to go. George Floyd has become the present-day martyr in a long line of martyrs. That’s proven how much a system designed to disenfranchise us are still in place. In a way, we have always been in the midst of an ongoing pandemic and yet to find a vaccine for that.

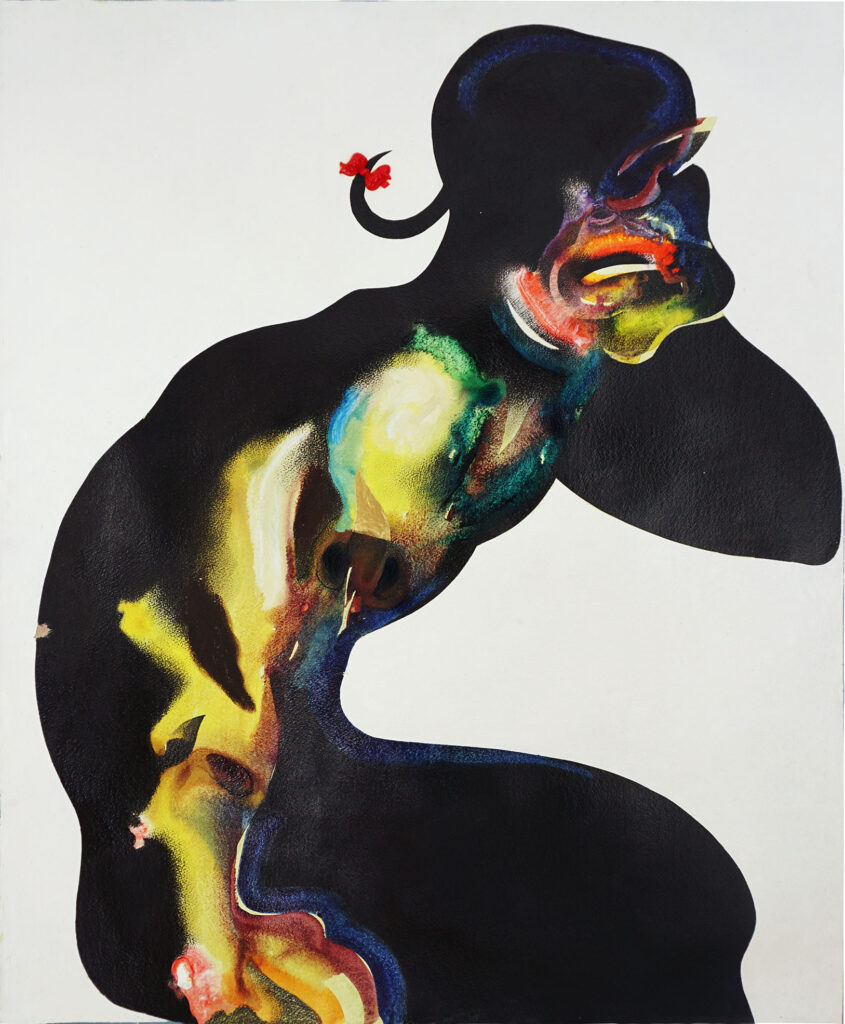

Onus (Anansi #5) ,” 51” x 59”, charcoal, distemper, watercolor, ink, coffee, acrylic, oil, oil stick, and gesso on paper, 2020

AMFM: What have you learned about yourself in 2020 and what are you most looking forward to in the new year?

JOHNSON: I guess I learned that I have loads of patience, not with myself, but with other people. I’m not sure if that’s a good or bad thing. I also learned that I have the potential to be a good teacher, I struggled with the thought. You can say that I am aware of the responsibility of that role, and I would hate to be a bad teacher. I doubted myself a lot until I finally got the chance to teach here at SAIC as a part-time faculty. This coming year, I wish to finally be able to socialize within the six feet periphery and without relying on a mask for safety. I still will be wearing them though for my own sake. I haven’t got the chance to experience Chicago in its fullest due to just being in grad school, I didn’t go out much during the two years here. I really want to see this historic city in all its glory.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST